The Range Rover Autobiography Ultimate parking in

the center of Ho Chi Minh City signals that its owner is hanging out somewhere

in the area. His year of birth (1978) is just about the only bit of his personal information M. (his

initial) agreed to be publicized. For such a young and successful entrepreneur,

this man is surprisingly secretive. He had successfully evaded the attention of

the Vietnamese media for years although his penchant for luxury is well-known

in the business world. He is also the man who brought Roll-Royce into Vietnam.

|

| M.'s Range Rover Autobiography Ultimate Edition. Courtesy of AutoTV. |

M.'s secrecy is understandable. In a country where

the median income per capita is a meager $1400 per year, a car costing from

$500 thousand to $800 thousand (second-hand) and $1.2 million to $1.7 million

brand new will draw much unwanted attention

wherever it goes. Many have used this to their advantage: Ms. Dương Thị

Bạch Diệp, a real estate developer, has become extraordinarily famous overnight

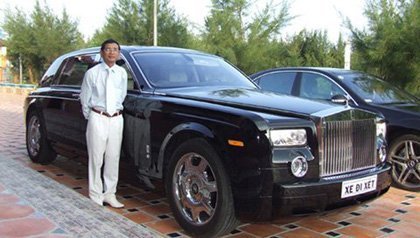

because she imported a brand-new Rolls-Royce Phantom in 2008. The same can be

said for Mr. Lê Ân who was not known outside of his hometown of Vũng Tàu until

he bought his own Phantom.

|

| Ms. Dương Thị Bạch Diệp and her Phantom. Courtesy of VietnamNet. |

|

| Mr. Lê Ân and his Phantom. Courtesy of VietnamNet. |

There are a total of 56 Phantoms in Vietnam but only

one of them (Ms. Diệp's) was imported straight from the factory. But if we

count other Rolls-Royces, the total number would almost double to 97. Apart

from the 56 Phantom saloons, there are also six Drophead Coupes, two Phantom

Coupes, 31 Ghosts and two antique cars from the Vietnam War. Even more astonishing,

of the 56 Phantoms, six of them are the ultra-exclusive "Year of The Dragon" Edition of which

there are only 33 in the world.

|

| A Phantom Drophead Coupe. Courtesy of VnExpress. |

|

| A Phantom "Year of The Dragon" Edition. Courtesy of VnExpress. |

It can be concluded that, judging on the overall

economy of Vietnam, the country's big spenders have invested an incredibly

large amount of money in the double-R brand. But most of them are doing it the

right way. A business partner of M. simply known as "Kar" chimed in

that Rolls-Royces are status symbols not just in Vietnam but everywhere in the

world, but the Vietnamese buyers are wrong in thinking that just owning a

Phantom makes them special. The real special cars are those that were specified

by the customers themselves. Of the 97 in Vietnam, sadly only one or two or

actually built to their owners' specifications.

"So basically, many of them have disregarded

the company's most basic principle: treating their customers as royalties. You

can have almost anything you want on a Phantom or a Ghost done according to

your taste, but instead you go and buy other people's taste," he said

frankly. "So are you really kings at all?"

While M. sat silent and observed the conversation, "Kar"

continued with his passion for Rolls-Royce. "If I can pay, and I wish I

can, my Phantom is going to put the ones in the Sultan of Brunei's garage to

shame," he laughed. "I really love the way they even take your feet

measurements to make sure you don't get cramped while sitting. That's why I

disagree with people who buy second-hand Rolls-Royces."

M.'s personal Phantom

EWB (Extended Long Wheelbase) is the first of its kind in Vietnam. The most special object on this car is a

clock made by Corum of Switzerland that has M.'s initials engraved on the dials.

The clock can also be unattached from the center console of the Phantom and

worn as a watch. He spoke of his plan to bring the real Rolls-Royce into Vietnam and how it had always been his dream

to put Vietnam on the luxury map of the world. "I want one thing and one

thing only: to bring the absolute perfection of the greatest luxury carmaker to

the Vietnamese people," he said proudly of his achievements in becoming

the brand's representative and opening their first showroom in Hanoi. His new

company, Regal Motor Cars, will also be the official dealer of Rolls-Royce when

the showroom is opened in September 2013. M. is right to be proud of his

victory, he had beaten Euro Auto - the official dealer of Rolls-Royce parent

company BMW - and many other prominent Vietnamese companies to secure the deal.

|

| M's Phantom EWB. Courtesy of VnExpress. |

M. has been successful so far in his career. Not

only in being recognized by Rolls-Royce but also in spreading his wealth around

for the good of the community. He is a philanthropist but does not call himself

a giver. "I try to do what I can," he said. "I just don't want

people to tell me what to do." M. has also been very successful in

polishing his name with garnering much attention. Near the end of 2012, rumors

that a "big player" is about to bring Rolls-Royce into Vietnam started

to surface. And when Regal Motor Cars was announced of the official dealer,

everybody apart from insiders were taken by surprise. Surely with his

"stealthy is healthy" business ethics, M. will keep winning.

*Updated: Since Rolls-Royce has recently opened their showroom, M.'s identity no longer needs to be concealed. He is Đoàn Hiếu Minh, Chairman of the Board of Regal Motor Cars.

*Updated: Since Rolls-Royce has recently opened their showroom, M.'s identity no longer needs to be concealed. He is Đoàn Hiếu Minh, Chairman of the Board of Regal Motor Cars.

.gif)

_copy.jpg)